It’s already not universal across websites. The easiest allow me to access them immediately with login required once a month or so. Some allow auto-completion of my userID and password without me having to do anything but hit the Login button. A few force me to type my password, disallowing any pasting or auto-completion. Several require that I prove I’m human before the login button becomes active. A few require 2FA. And others somewhere in between. I seriously doubt that the passkey system will be vastly different than the variety of methods already in use today.

deep in the depths of memory, I recall a hardware device provided security code to login to PayPal, a rolling code if I recall.

Seemed so simple then in comparison to the absolute mess today.

- website logins that have varied requirements, some demand min 16 chars, others reject if >12, some require username or phone and not email, things Safari can’t quite cope with, so needing another PW manager. 2FA where TEXTs or emails don’t arrive, very productive altogether

So, “welcome” another layer to deter users.

That’s effectively what a FIDO key, but with no display!

nirvana would be a SSO Passkey that is Universal, cross every platform/system, not adding something new whilst everything else remains.

then life may be easier for Adam as it would enable seniors to self manage to a greater degree.

“ Helping Senior Citizens Reveals Past Apple Lapses and Recent Improvements “

How we’ve ‘ progressed ‘ since my first SE/30, where computing was slower, but productivity wasn’t hobbled.

Passkey won’t fix this, but I seriously considered divorcing from my iMac, MacPro, 3 iPads, until the MacStudio arrived. ![]()

Much of that due the inconsistencies in installing apps where there is massive divergence in enabling Security & Privacy permissions, screens pop and vanish. icons have to be dragged.

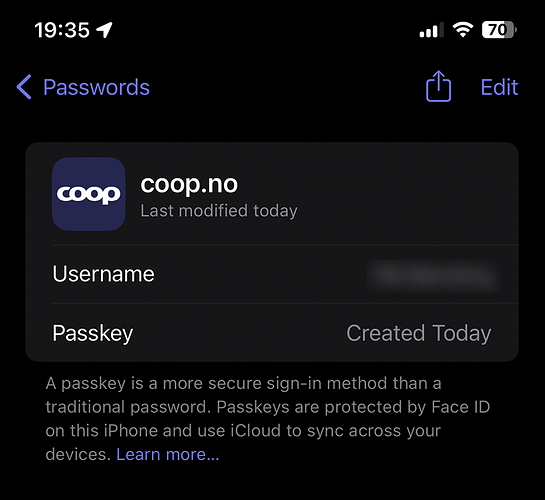

Got my first passkey today on iPhone. It was an login to a app I use at the local grocery store that prompted me if I would like to save a passkey.

Does anyone have thing to add to these concerns expressed by Jeff Johnson:

I respect Jeff and his work immensely. StopTheMadness absolutely and dramatically improved my web experience. He’s very much a Cory Doctorow for the Apple ecosystem: he speaks out early, loudly, and sometimes taking the extreme worst case—and, sadly, he’s often right to do so.

On passkeys, I think he’s expressing a lot of reasonable frustration for anyone who doesn’t want to slide into the warm embrace of iCloud and Apple’s default choices. It is an industry standard. The passkeys, by design, will be able to be managed and moved around in different ways. 1Password I hope will be one of the methods by which we can backup and sync apart from iCloud. Some of the passkey infrastructure is OS-embedded in order to provide the kinds of out-of-band security elements required, so some details remain to be sorted out for non-OS provided passkeys.

It’s definitely an issue now, though: there’s a short-term lock-in without details about how the long-term plan will emerge for portability and syncing. However, for most users, passkeys are a huge security improvement and, based on talking to 1,000s of Mac users over many years, most Mac users are all-in on the Apple ecosystem.

For sure, iCloud used to be very rough around the edges. I find it more reliable in the last couple years than ever before. I had a recurring iCloud Drive problem (saving a live file would often reload the last version of the file; couldn’t find anyone else with the problem; Ventura fixed it) that was my last rough edge.

I absolutely disagree with the intent of passkeys as Jeff is expressing them. It’s a significant security improvement over the current method. We’re in early days and that may deter some people from adopting them now until there’s better portability.

I also disagree with him about Yubikeys. It doesn’t fit his use case at all. These keys are intended to be with one at all times (like on a keychain) and designed to provide the requirement of physical proximity. The vast majority have no biometric component and that fits the design remit: they are meant when you know you can secure physical access and want it to be portable—works on any device and OS with supported websites or other components. The next level up is really using passkeys with biometrics: same technology, more secure interface that still requires an attacker to gain access to your hardware, and the biometrics add one additional level of protection.

I’d say Johnson is a member of a relatively small group of Apple users: people who are developers and people who are 70s-style computer hobbyists. Now that Apple has transformed its brand and most of its products into lifestyle and luxury statements–in Apple historical terms, Ive not Woz–passkeys will be a major benefit for both the vast majority of Apple’s customers and for all users of services that require logins. The faster we can all get away from passwords and SMS-based 2FA, the better.

Yes, yes, yes!

I’m still interested to learn how Apple is going to solve the Find My app issue if you’ve lost your phone and your phone is the only Apple ID device (or the only one with you.) For now, you can borrow an iPhone or iPad and log in to your Apple ID with a password in the Find My app, or in a web browser on a computer, without triggering the 2FA approval notification to a trusted device/trusted contact, so you can track your lost device. What happens when your Apple ID uses passkeys? Will you still be able to do this, and how?

Passkeys appear to be an improvement in the case of stolen/leaked/breach attacks that harvest a bunch of passwords in that they depend on public/private key pairs and if the bad guy steals your public key from google or wherever it doesn’t really let him log into your account because public is useless without the private one which only you have. However…if one has a good (i.e., long) password and the website has adequate security of their encrypted password database and there aren’t any previously unknown zero day flaws in their encryption algorithms then the long password pretty much protects you for a long time…hence unless you’re a specific high value target it’s not worth the computer time and expense to crack your password and the bad guys will just move on.

As Jeff says…they currently depend on iCloud which as we know is somewhat unreliable…and the number of websites that can use a passkey instead of a password is still pretty limited and will likely stay that way for years. I can see a day way in the future when most sites are using passkeys…and the various password managers (which are used by many of us to store a lot more than just passwords)…have all been updated to both adequately store, protect, and allow backup and restore on the user’s end of said passkeys…then they will be a good thing.

In the end though…for the vast majority of people who have sufficiently long passwords…it appears to me that the advantages of them over password are over emphasized by the people promoting them…

Yes…in a perfect world they’re better than passwords because of the enforced length and the you need the private key part…but it’s not a perfect world…and won’t be one for a long time. One of the things I learned way back in engineering school and that was relearned through 20 years in Uncle Sam’s Canoe Club driving submarines…and then again in my days as a budget guy and then an IT sysadmin…is that better is the enemy of good enough…and thus for many situations good enough is…well…good enough.

I hate to disagree…and I’m only partially anyway. Yes…in theory it is a significant improvement…but that’s much like looking t photos at 1:1 resolution in Lightroom and declaring one better than the other. The public/private key system makes it more secure…but the real question is whether that increase in security is meaningful. Assuming that the user is reasonably competent and has an adequately secure password…which in 2023 essentially only means long enough…and assuming that the website has decent security for its hashed password database, which most probably do as in 2023 few websites roll their own security…they use generally accepted and vetted libraries to do that because most web devs aren’t security experts…then at worst the website loses a copy of the encrypted database of hashed passwords. Given long passwords and not being a particularly attractive target like the President or AOC or whoever…the vast majority of users are of sufficiently low priority that the long password really provides good enough security since it isn’t worth the expense of trying to crack the password for the gain you will get out of it…in other words the vast, vast majority of users are low value targets. So…while technically you’re correct and it is better…in most cases this is an example of better is the enemy of good enough. So…for any reasonably technically competent user…switching to passkeys probably isn’t worth it until (a) the tech improves so they are easier to deal with and (b) they are mostly ubiquitous across the web…and that last element will require years at least. The passkey tech is simply too immature at this point to be worth the slight gain for a considerable effort IMO.

The qualms and questions about passkeys on this comment thread are illuminating. At best, the industry advocates have done a terrible job communicating when, why, and how to use passkeys. If TidBITS readers aren’t sure about passkeys, it’s not a promising sign for adoption of the technology. At worst, it may be a tech solution that has real benefits but never quite makes it beyond niche applications. (PGP-encrypted email, I’m looking at you!)

From a communications standpoint, if the general perception of passkeys becomes “It’s too complicated” in these early days, especially due to tech media hype, it may not matter if passkeys work well in the future. Once the original Newton became a punchline, it didn’t matter that the later eMate and the MessagePad 2100 were great devices.

Coincidentally, there was an interesting article today at Ars Technica about Google’s implementation of passkeys. I’m not sure that snarky headlines like “Google passkeys are a no-brainer. You’ve turned them on, right?” are helpful to the cause, especially for a 2,500 word article explaining the no-brainer.

(Sorry for deleting my previous comment. It was a little too clunky and really should have been a couple of comments.)

Especially when you’re a user who avoids all things google like the plague (Arc will NOT change the way I work on the web). I do like Ars in general, though.

I completely agree with Neil’s last two posts. I think there are a few key metrics: Is your bank or credit union using them? Is Amazon using them? Is Social Security using them? Is Medicare using them? Is the Department of Defense/VA using them?

For me, the answer to all those questions is currently no. And the only way I can get my wife to use good passwords is if I set them and “program” them into Safari so that she has to expend virtually zero effort to use them.

Well, she should be happy with passkeys then. That’s certainly where passkeys are better. They are always strong; they will be easy to use. Easier than user ID/password.

Those are two big assumptions for most people. Competence about passwords is generally not high.

One sure advantage of passkeys is that this is no longer a thing, nor is phishing for passwords. You can’t phish for a passkey.

FWIW, when it comes to iCloud Keychain, it has been absolutely reliable in my experience for quite a while.

I agree that Apple, Google, Microsoft, and the FIDO Alliance have done a very poor job of explaining passkeys and how they will work. I think they should have waited to publicize them until more of the details were worked out, particularly about how they’re going to work across platforms.

I wouldn’t read too much into the comments from the public though. It seems to me that many are knee-jerk reactions to rejecting anything that is new and different, and a lot of objections seem to be based on misunderstandings and misconceptions from people who haven’t taken the time to learn about passkeys. A lot of the blame, of course, lies with the poor communication by Apple, Google, and Microsoft, but individuals do bear some responsibility to not make claims based on ignorance.

I find your examples (other than Amazon) kind of amusing. In my experience, financial institutions and the government tend to be laggards when adopting modern security practices.

Actually…competence about passwords is pretty easy today…in reality the o ly thing that matters is length. Even standard dictionary words…inypterspersed with the first leyyer upper case, separated by & or $ or * and a digit or two on the end are just fine. Get the length to 20 or so and the only way it’s going to be broken is brute force…and for the vast majority of people it is simply not cost effective to try and crack it. As I said…most websites are no rolling their own security stuff…they’re using standard packages which for the most part are vetted…so at worst the encrypted password database gets leaked or stolen or whatever. That really doesn’t matter if your individual password is essentially unbreakable. We see ll these leaked password lists…but we’re they leaked in the clear or did they run Jon the Ripper or similar on it and break all the 8 character ones…that’s trivial but won’t crack any of the adequately long passwords.

As I said…from a purely technical standpoint passkeys are better…but as they exist today they re the enemy of good enough…to few sites, too many hurdles t9 backing them up and syncing them or moving them to another device, etc…eventually they will be ubiquitous and make sense but today they don’t for most people because of the growing pain issues. YMMV.

I know all this, but it remains that people in general do not practice this, do not even know this, still tend to use short, memorable passwords, reuse them across sites, etc. Recent article: Study reveals top 20 most used passwords; 83% can be cracked in a second - 9to5Mac

The company notes that “despite growing cybersecurity awareness, old habits die hard. The research shows that people still use weak passwords to protect their accounts.”

I would say most non-technical people I know still try to create their own passwords when confronted with a prompt, even on iPhone or iPad, when iCloud Keychain tries to recommend a good one.

When you need to manually enter a password – as for example when I’m logging into my Mac – anything more than about 10 characters gets to be a problem, especially if it’s randomized. It can take me several minutes to enter the roughly 20 characters of my WiFi password, because it’s on a paper master and I have no way to transfer a digital version to a new phone or device.

I now use suggested passwords much of the time, but I have found they may break when web addresses change, or when something else goes wrong.